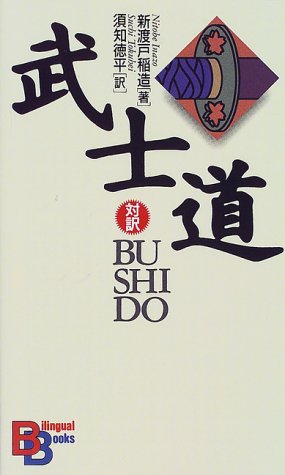

『武士道 Bushido 』-新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobé)-

Chapter 03

(Rectitude or Justice 「義」武士道の光輝く最高の支柱)

Bushido, the Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe

[Book]

[reading]

・Chapter TOP 新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobé)TOP

・Chapter 00(Prefaces 序文)

・Chapter 01(Bushido as an Ethical System 武士道とは)

・Chapter 02(Sources of Bushido 武士道の源)

・Chapter 03(Rectitude or Justice 「義」)

・Chapter 04(Courage, the Spirit of Daring and Bearing 「勇」)

・Chapter 05(Benevolence, the Feeling of Distress 「仁」)

・Chapter 06(Politeness 「礼」)

・Chapter 07(Veracity or Truthfulness 「誠」)

・Chapter 08(Honor 「名誉」)

・Chapter 09(The Duty of Loyalty 「忠義」)

・Chapter 10(Education and Training of a Samurai 武士は何を学びどう己を磨いたか)

・Chapter 11(Self-Control 人に勝ち己に勝つために)

・Chapter 12(The Institutions of Suicide and Redress 「切腹」)

・Chapter 13(The Sword, the Soul of the Samurai 「刀」)

・Chapter 14(The Training and Position of Woman 武士道が求めた女性の理想像)

・Chapter 15(The Influence of Bushido 「大和魂」)

・Chapter 16(Is Bushido Still Alive? 武士道は蘇るか)

・Chapter 17(The Future of Bushido 武士道から何を学ぶか)

・[修養]、

・[自警録]

the most cogent precept in the code of the samurai. Nothing is more loathsome to him than underhand dealings and crooked undertakings. The conception of Rectitude may be erroneous—it may be narrow. A well-known bushi defines it as a power of resolution;—"Rectitude is the power of deciding upon a certain course of conduct in accordance with reason, without wavering;—to die when it is right to die, to strike when to strike is right." Another speaks of it in the following terms: "Rectitude is the bone that gives firmness and stature. As without bones the head cannot rest on the top of the spine, nor hands move nor feet stand, so without rectitude neither talent nor learning can make of a human frame a samurai. With it the lack of accomplishments is as nothing." Mencius calls Benevolence man's mind, and Rectitude or Righteousness his path. "How lamentable," he exclaims, "is it to neglect the path and not pursue it, to lose the mind and not know to seek it again! When men's fowls and dogs are lost, they know to seek for them again, but they lose their mind and do not know to seek for it." Have we not here "as in a glass darkly" a parable propounded three hundred years later in another clime and by a greater Teacher, who called Himself the Way of Righteousness, through whom the lost could be found? But I stray from my point. Righteousness, according to Mencius, is a straight and narrow path which a man ought to take to regain the lost paradise.

Even in the latter days of feudalism, when the long continuance of peace brought leisure into the life of the warrior class, and with it dissipations of all kinds and gentle accomplishments, the epithet Gishi (a man of rectitude) was considered superior to any name that signified mastery of learning or art. The Forty-seven Faithfuls—of whom so much is made in our popular education—are known in common parlance as the Forty-seven Gishi.

In times when cunning artifice was liable to pass for military tact and downright falsehood for ruse de guerre, this manly virtue, frank and honest, was a jewel that shone the brightest and was most highly praised. Rectitude is a twin brother to Valor, another martial virtue. But before proceeding to speak of Valor, let me linger a little while on what I may term a derivation from Rectitude, which, at first deviating slightly from its original, became more and more removed from it, until its meaning was perverted in the popular acceptance. I speak of Gi-ri, literally the Right Reason, but which came in time to mean a vague sense of duty which public opinion expected an incumbent to fulfil. In its original and unalloyed sense, it meant duty, pure and simple,—hence, we speak of the Giri we owe to parents, to superiors, to inferiors, to society at large, and so forth. In these instances Giri is duty; for what else is duty than what Right Reason demands and commands us to do. Should not Right Reason be our categorical imperative?

Giri primarily meant no more than duty, and I dare say its etymology was derived from the fact that in our conduct, say to our parents, though love should be the only motive, lacking that, there must be some other authority to enforce filial piety; and they formulated this authority in Giri. Very rightly did they formulate this authority—Giri—since if love does not rush to deeds of virtue, recourse must be had to man's intellect and his reason must be quickened to convince him of the necessity of acting aright. The same is true of any other moral obligation. The instant Duty becomes onerous. Right Reason steps in to prevent our shirking it. Giri thus understood is a severe taskmaster, with a birch-rod in his hand to make sluggards perform their part. It is a secondary power in ethics; as a motive it is infinitely inferior to the Christian doctrine of love, which should be the law. I deem it a product of the conditions of an artificial society—of a society in which accident of birth and unmerited favour instituted class distinctions, in which the family was the social unit, in which seniority of age was of more account than superiority of talents, in which natural affections had often to succumb before arbitrary man-made customs. Because of this very artificiality, Giri in time degenerated into a vague sense of propriety called up to explain this and sanction that,—as, for example, why a mother must, if need be, sacrifice all her other children in order to save the first-born; or why a daughter must sell her chastity to get funds to pay for the father's dissipation, and the like. Starting as Right Reason, Giri has, in my opinion, often stooped to casuistry. It has even degenerated into cowardly fear of censure. I might say of Giri what Scott wrote of patriotism, that "as it is the fairest, so it is often the most suspicious, mask of other feelings." Carried beyond or below Right Reason, Giri became a monstrous misnomer. It harbored under its wings every sort of sophistry and hypocrisy. It might easily—have been turned into a nest of cowardice, if Bushido had not a keen and correct sense of

Read文献、

book文献

TOP

日本の魂ー日本思想の解明ー

日本的思考の根源を見る。

”忠義”は追従ではない。”名誉”は求める心である。

(第三章 義-あるいは正義について)

サムライにとって、 卑怯な行動や不正な行動ほど恥ずべきものはない。

(第九章 忠義)

武士道は、われわれの良心を主君の奴隷となすべきことを要求しなかった

(第十章 武士の教育)

武士道は経済とは正反対のものである。それは貧しさを誇る。

(第十一章 克己)

心の奥底の思いや感情—特に宗教的なもの—を雄弁に述べ立てることは、日本人の間では、それは深遠でもなく、 誠実でもないことの疑いないしるしだと受け取られた。

(第十四章 女性の教育と地位)

妻がその夫、家庭そして家族のために身を捨てることは、男が主君と国のために身を捨てるのと同様、自発的かつみごとになされた。

|

・新渡戸稲造

第1弾「世界を結ぶ『志』~新渡戸稲造の生涯~」、

第2弾「未来につながる『道』~新渡戸稲造の武士道~」、

第3弾「すべてに根ざす『愛』~新渡戸稲造の苦悩~」、

・ 新渡戸稲造の至極の名言集

・「新渡戸稲造の名言」20話

| |

・Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nito(1-18)

・Bushido: The Soul of Japan by Inazo Nitobe(1-18)

・武士道「BUSHIDO」Japanese Ver.

・≪AI朗読≫武士道

・【武田鉄矢】『武士道』完全版

|

Bushido, the Soul of Japan

『武士道は定式化されたものではないが、昔もそして今も、日本人を鼓舞し、わが国を動かす原動力なのである』

日本人が日本人たりえる所以。

国家としての歴史的哲学体系を持たない日本の、現代社会においても尚、我々の血肉となり、在り続ける道徳律の根幹は「武士道」にあり。

日本人 新渡戸稲造博士が世界に発信した日本人論。

世代と国境を越え今なお読み継がれている世界的ベストセラー。

西洋・東洋の文化・哲学・思想と照らし合わせながら、その特異性と唯一無二の行動規範・心の拠り所を詳細に解説した普遍の書が、完全現代語訳、プロフェッショナルのナレーションで今蘇る。

21世紀。世界第三位の経済大国であるわが国日本。

政治的にも文化的にもより身近に世界と対峙する現代においてこそ、われわれの心の中に脈々と流れ続ける、日本人が日本人足らしめる「武士道」の精神を紐解く時なのではないだろうか。

本書は1世紀の時を超えた今も尚色褪せること無く、むしろその博識と見解、交える事例とそのユーモアに溢れた表現により現代人の我々にも実に痛快に日本の心「武士道」を理解させてくれる。

「武士道」がいつどのようにして始まったのか、それはどんな特徴を持ち、どのようなことを教えようとしているのか、武士以外の一般民衆にどのような影響を与えたのか、その影響がどれほど永く続いているか。

様々な角度・キーワードで武士の心得、さむらいの心の在り方をリレー形式で綴っている。

世界有数の犯罪率の低さ、大災害時での規律、自発的な他助の精神と行動は時代を超えて、親から子へと語り継がれてきた「道徳律」が存在し続けていることを如実に表している。

知っているようで知らない「日本の心」が、ここに明かされている。

内容抜粋

「今何とおっしゃいましたか?」と敬愛する教授は尋ねた。

「日本の学校には宗教の教育がないということでしょうか?」

そうですと答えると、教授は驚いて足を止めた。そして、今でも耳から離れない声音で、重ねてこう聞いた。

「宗教がない! だとしたら、いったいどうやって道徳を教えるんですか?」

この質問に私は意表を突かれ、とっさに答えを返すことができなかった。というのも、子どもの頃私が学んだ道徳というのは、学校で教わったものではなかったからである。私は、自分の持っている善悪正邪の概念を作り上げているさまざまな要素をひとつひとつ分析してみて、ようやく、それらを私の中に植えつけたのは「武士道」であったことに気づいた。

武士道とは、武士が守るよう求められる、もしくは、そう教えられる道徳的な作法である。文字に書かれたものはなく、せいぜい口伝えで伝えられた格言や、有名な武士や学者が書いたものが残されている程度である。

多くの場合そうしたものさえなく、しかしだからこそかえって深く心に刻まれ、守るべき掟<<おきて>>として強い拘束力を持っていた。ひとりの優秀な頭脳が考え出したものでもなければ、ひとりの高名な人物の生きかたが手本となってできたものでもない。数十年、数百年に及ぶ武士の歴史の中で自然に醸成されたものである。

「義は、道理に従ってためらうことなく、何をなすべきかを決断する力である。死ぬべきときは死を選び、討つべきときには討つことを選ぶ力である」

「戦いの真っただ中に飛び込んで討ち死にするのはいともたやすいことで、身分の卑しい者にもできる。生きるべきときは生き、死ぬべきときにのみ死ぬのが本当の勇気である」

「義に過ぎれば固くなる。仁に過ぎれば弱くなる」

「礼法の要点は精神を養うことにある。礼をもって静かに座っていれば、どんな乱暴者でも危害を加える気になれないほどに」

仁愛や謙譲の精神から生まれた礼儀は、他人に対する思いやりから生まれて、人への同情心を品よく優雅に表現するものだからである。

「心だに誠の道にかないなば祈らずとても神や守らん」

「忠ならんと欲すれば孝ならず、孝ならんと欲すれば忠ならず」

命は主君に仕えるための手段だと考えらえており、その理想形は、名誉のために命を捨てることであった。

「おのれの魂という畑が、優しい心で揺れ動くのを感ずるか? まかれた種が芽吹こうとしているのだ。言葉でそれを妨げてはならぬ。静かに、ひそやかに、自ら芽吹くのを見守っているのだ」

「死を軽<<かろ>>んずることは勇気のいる行為である。しかし、生きることが死よりもつらいときに、あえて生きることこそが本物の勇気である」

「かくすればかくなるものと知りながら やむにやまれぬ大和魂」

目次

訳者序文

初版への序文

改訂第10版への序文

新渡戸博士の『武士道』に寄せて

第1章 道徳体系としての「武士道」

第2章 武士道の源

第3章 「義」――あるいは正義について

第4章 「勇」――勇敢さと忍耐力

第5章 「仁」――慈愛の心

第6章 「礼」

第7章 「誠」――正直さと誠実さ

第8章 「誉<<ほまれ>>」――あるいは名誉について

第9章 「忠義」

第10章 武士の教育と鍛錬

第11章 自制心

第12章 切腹と敵討ちという制度

第13章 刀――武士の魂

第14章 女性の教育と地位

第15章 武士道から大和魂へ

第16章 武士道は今も生きているか

第17章 武士道のこれから

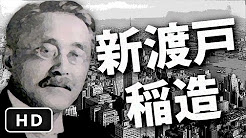

新渡戸稲造(Inazo Nitobe)

文久2年(1862年)、藩士 新渡戸十次郎の三男として南部藩(今の岩手県)に生まれる。

幼少期より東京英語学校に学び、少年期は、後に「代表的日本人」の著者でもある内村鑑三らとともに札幌農学校へ入学し学業を磨いた。

明治維新後はアメリカ・ドイツに渡り農政学を始め様々な研究に従事。

台湾総督府技師として台湾の殖産に携わり功績を挙げる。

国際連盟事務次長としても国際的に活躍。帰国後は様々な学校の教職を歴任した後、東京女子大学初代学長にもなる。

本書「武士道」は英語のみならずポーランド、ドイツ、ノルウェー、スペイン、ロシア、イタリアなど、主として欧米の多様な国の言語に翻訳され世界的ベストセラーとなる。旧五千円札の肖像画の人物としても有名。

TOP

朗読,Read 朗読,Read

|

朗読,Read

朗読,Read

朗読,Read

朗読,Read